When announcing their company, founders should be aware of the point in the narrative cycle their category is in. This is something that we believe requires craft, care, and intentionality, and a topic we often work with our founders on at Compound.

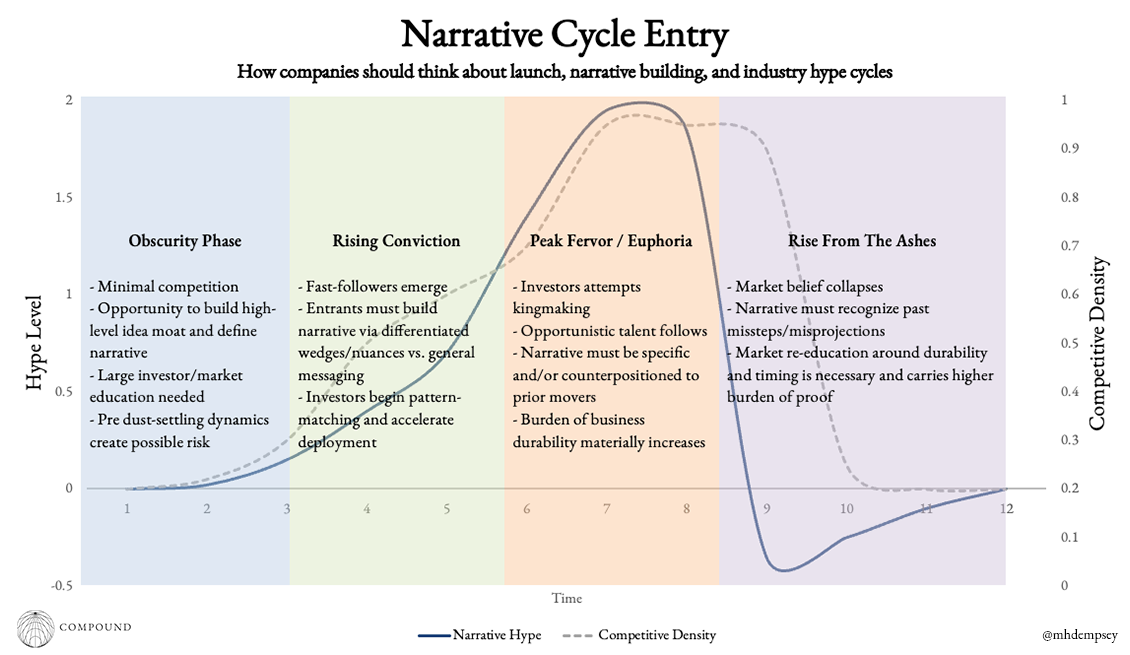

We can simplistically think of narrative cycles as having four stages:

The Obscurity Phase: The early stage in which an area has minimal hype, a small number of people who care about it, and minimal competition. This means founders must educate the market but also are forced to build narrative ahead of points of certainty in the overall market.

The Wave of Rising Conviction & Consensus: The middle stage where hype begins to pick up, multiple competitors are helping to push a variety of adjacent narratives, and talent and investors are rapidly being converted from curious to believers.

Peak Fervor & Euphoria: The late stage where hype, consensus, and competitive density is highest, resulting in difficult differentiation, excess capital, and lots of opportunistic participants

Rise from the Ashes: The post-blow off top where expectations are reset and a wave of believers have now converted to doubters, often resulting in excess negativity from the media, talent, investors, and broader public on either the space or the viability of companies operating in a given segment of technology.

These areas progress from one to the other, and with each of them there are different lessons and strategies that must be applied in order to properly launch your company successfully and enter the conversation against varying levels and types of noise.

The Obscurity Phase (early)

The Obscurity Phase of a narrative cycle has a lot of range but is generally where magic can happen of either defining or expanding the awareness and possible reality of a category.

These days this part of a narrative cycle lasts 12-36 months, with the first 12 months soldiering on fairly undetected.

A main benefit of launching in the birth of a narrative cycle is that you can build an idea moat and narrative capture around a given category at a high level (think back to areas like NewSpace, Government Tech, Deep Learning, Synthetic Biology). These areas are either positioned based on customer type or science-type at the highest level.

By doing this, as a company you have the ability to focus on a wider range of coverage options/narrative surfaces in comms/marketing. Companies can build narrative around the generalities of their industry which many people care about and eventually hone in over time on the specific narrative points related to their product or a feature in their product that perhaps only sophisticated buyers or insiders care about.

The other core benefit is that there is often less competition for mission-driven or industry-specific talent before death by a thousand cuts emerges (people will settle for working in Space, not necessarily Space-based Comms, or Climate, not necessarily Small Modular Reactors, etc.)

Lastly, early market leaders with execution have the ability to accumulate capital as the narrative hype continues (more on this soon) and become an early Schelling Point Company or category leader as investors attempt to kingmake companies faster than ever before.

There are however drawbacks of being early to a given narrative cycle.

Entering a narrative cycle early leaves your company open to being copied, out-executed, and/or to publicly creating lessons learned for fast-followers. This happens more than ever at a time where any given startup typically has 2-4 venture-backed competitors within ~24 months of founding.1This is also why early parts of narrative cycles only last ~12-36 months now versus closer to 24-48 months in prior times.

Obscurity Phase companies are also possibly unable to build a commercialization moat of sufficient scale, which means that as the customer base expands, despite being early to a category, later-movers can acquire net new customers and build a larger business on the back of learnings and counterpositioning/outpositioning your product on a single vector that matters most to the next wave of customers.

Combining these points, by being early you likely are ahead of any “dust settling” events that could force you to pivot or re-orient your company and its narrative. This has been in some ways felt by early AI wrapper companies that were anticipating slower takeoff of model performance or different strategic approaches to the application layer by the frontier labs.

This also previously was felt across areas with slower than anticipated production takeoffs like robotics infrastructure, space software, biomanufacturing as a service, and many more (all basically made an implicit bet that robots/satellites/synbio/etc products would all scale materially faster and with more company diversity than they did, leading to less commercial traction and less of an ability to work within the constraints of showing commercial progress every 18-36 months for investors).

The Wave of Rising Conviction & Consensus

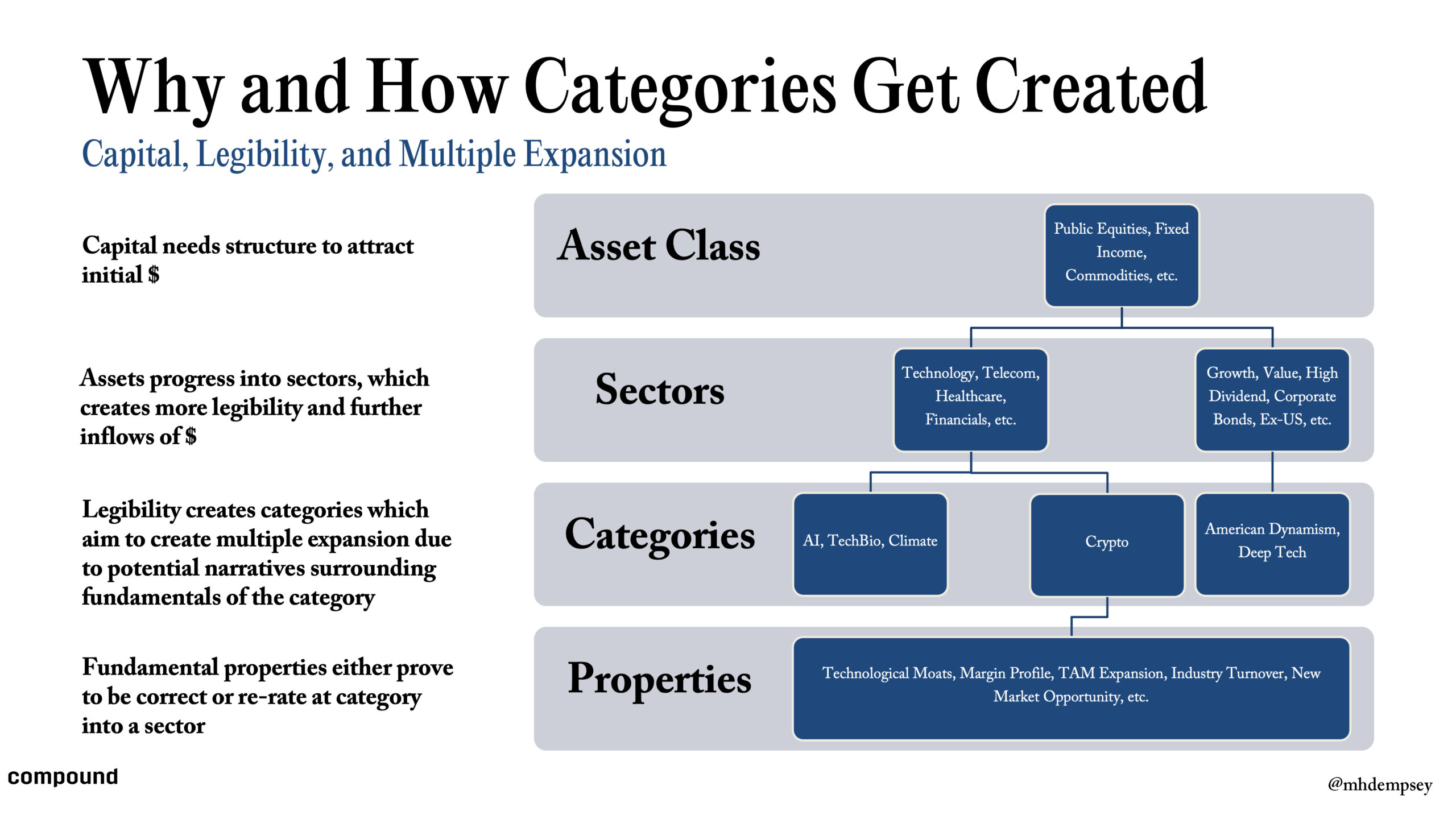

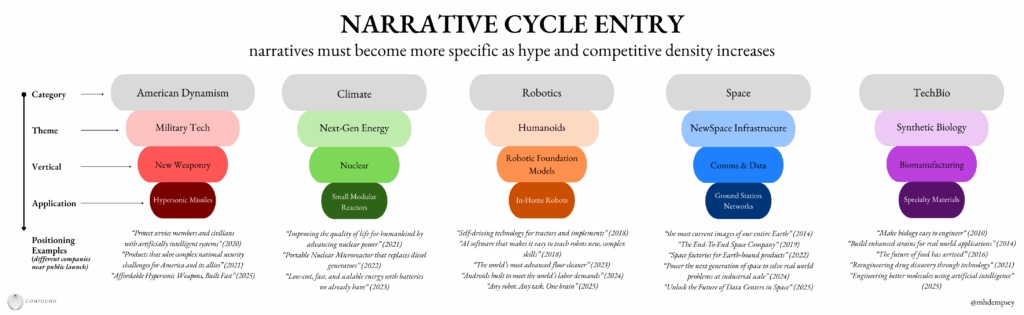

In startups and all of technology markets, narratives come in waves and as category creation occurs companies are either able to be the Schelling Point Company of the broader category or must aim to dominate a micro narrative within said category.

The wave of rising conviction has a longer arc in which you see both the scaling of initial flagship/early-mover companies, as well as the early funding of fast-following businesses that creates the first signs of narrative exhaustion. These fast following companies typically anchor on the same narrative points but perhaps are more “central casting” teams that raise large sums of capital in order to “catch up” to early movers on a variety of vectors.3This happens because VCs see another company working and want to back competitors, often trying to fire larger capital cannons thinking that money creates speed. It does not.

The general public, investors, hires, and customers are often left tired, unimpressed, and/or skeptical as they have spent the last 24 months feeling like a space went from “expanding” to “crowded” as multiple companies attempt to ride the same higher order narrative over and over again.

I wrote about this dynamic in Open Source AI Business Models & Brand Moats with respect to Inflection’s attempt to be a Frontier AI Lab:

Nobody has perhaps understood the value of these brand building dynamics and embodied this tactical approach better than Sam Altman who I would argue is running perhaps the largest scale tech-oriented PR campaign in history.

It’s likely that personifying the entire movement is a window that has closed, though others such as Mustafa Suleyman at Inflection are still attempting to do so by doing something I haven’t ever seen a pre-PMF startup founder do, publishing a book.

I largely view these broad-based “AI Thought Leader” attempts as futile efforts at this point, and instead believe that companies should aim for differentiating and honing their core message surrounding their company instead of boiling the entire AI ocean.

(This doesn’t mean that Sam/OpenAI has “won” AI, just that it’s not really feasible or worthwhile for a startup to attempt to capture that zeitgeist in this moment when OpenAI has a clear lead)

Via Compound 2024 Annual Meeting4Before investors in the fast followers get angry, this isn’t a perfect chart nor meant to position fast followers as worse companies

Because of this, for most founders, launching their company in the middle of the wave forces them to be more precise and explicit surrounding what core sets of beliefs they have that others do not OR why a more narrow narrative is still as important (or more important) than the higher level narrative owned by the incumbent early movers.

Using the prior primitives as examples, NewSpace post SpaceX ascension (2010-2016) quickly fragmented into satellite companies (which moved more into proprietary data platforms), launch, in-space manufacturing, and comms.

There are similar patterns in many other areas.

The benefit of launching in the middle of a wave is that if you are able to communicate these nuanced differences, it allows you time to see more settling of the dust per above that others have not, while also benefitting from the ground work of broader market education that the companies before you have done. Though, this also means that there is higher burden of proof on why your approach is right and why others’ is wrong, less valuable, or less interesting.

I find it best for founders attempting to do this to use their investors or former employees at early mover companies to understand how/why companies did or did not resonate with the broader public, customers, investors, and talent.

As the middle of the narrative cycle begins to crescendo the narrative positioning begins to similarly act as a wave to ride for founders.

The first 5-10 players in a given idea space often recognize if they are not the Schelling Point Company they must ride a more macro narrative down into specificity. This can broadly be viewed in the graphic below as a progression from Category all the way down to the core application or product.

Examples of this could be viewed through a set of companies that start as Climate companies then progress towards next-generation energy before moving specifically through to nuclear and eventually to Small Modular Reactors, with the world-building narratives surrounding the specific technology.

We can also see a similar movement towards specificity of American Dynamism → Military Tech → New Weaponry -> Hypersonic Missiles

If there is large or growing commercial appetite, we often can just see a straight jump to hyper vertical narrative space that is easy to parse like “AI for Legal/finance/etc.”

The middle of the narrative cycle is perhaps most difficult because it can be different if you are in the “early middle” vs. “late middle” part of the cycle, and thus navigating how and when to make this progression as a company is a game of chess that often requires execution as the burden of proof rises the longer a narrative and company has been in the zeitgeist.

We find the best teams are able to continue to flood the zone with marketing and comms over long periods of time in order to crystallize themselves as one of the core owners of their given idea moat. This is not trivial and requires treating external marketing as a first class in the org, both ideologically and with resources.

Peak Fervor / Euphoria

When an area reaches a level of consensus/fervor a slew of even later followers emerge while another cohort of companies pivot into the hot idea space.

We saw this in 2021 with crypto as a variety of companies slapped blockchain/crypto dynamics onto existing company structures.5Thank God we don’t say Web3 anymore.

We saw it again in 2023/2024 when a variety of companies raised large rounds to capitalize on the scaling of diffusion models and the success of Midjourney/Dall-E/Runway in order to build new types of “creative AI” businesses that basically came and went on twitter (while raising tens of millions of dollars along the way).

And we’ve most recently seen it in 2025 with a variety of companies moving into codegen across various angles chasing narratives from enhanced IDEs (cursor/windsurf) to pureplay autonomous codegen (Devin/Codex) to “app making” (lovable/v0/bolt). There are a variety of companies that are not these flagship products that all are/have raised in similar fashion surrounding code in the past 12-24 months.

While across each of these examples, each company attempts to differentiate at launch with a given feature (remember Ideogram launching with good text generation as the core differentiator on imagegen) or in a given vertical space (v0 for UI, Replit for webapps, etc.) any thoughtful person should have a core belief that there is likely high convergence coming in the paths for many of these companies.

In order to successfully summit a peak of a narrative cycle you must have meaningfully differentiated product in order to rise above any noise or massive distribution to win in guerilla warfare. You also likely have to pair the large marketing resources with a very high velocity of shipping such that the message does not get stale nor does it feel thin/unsubstantiated.

Entering at peak fervor allows for some ability to tactically find white space (both in reality and narratively) but requires a fairly relentless editorial calendar paired with execution. It may simplistically feel that this is the worst time to enter, but it also is a time that greatly benefits those able to push on narrative building well or those able to counterposition against the strongest of narratives and win over a small subset of believers.

The downside of entering at peak fervor however is that it too often can be the result of waiting too long to launch or un-stealth or by being a candidly undifferentiated fast follower that never gets off the proverbial ground with users.

Rise from the Ashes

Tech does a very good job of overpromising and underdelivering in the short-term which often can create very aggressive periods of disillusionment, resulting in a hard reset of hype and belief across the entire market in a given category. It is at these moments that is most difficult for founders to launch, but at times, most advantageous if the cycles we’ve come to love repeat, with a small subset of phoenix’s rising from the ashes of a dead narrative.

Doing this is admittedly rarely a choice and more often is a reality of collapse or a founding team’s obsession in the face of all uncertainty.6I know, I’m romantic to believe this still exists, right?

After the excesses and disappointment/disgust from peak fervor dissipate, a group of people will emerge that are waiting to be properly wowed in order to reshape their world view on a category, technology, or idea. The best companies are able to make these previous failures a necessary prequel to their founding story.

If a company does the above, this can create a new cycle that re-rates the category and allows the company to accumulate lots of capital to attempt to compete against the onslaught of fast followers (and we’re off to the races again on the narrative cycle).

Crypto has historically been good at this, re-trying old ideas with each cycle while sprinkling in different product mechanisms that re-skin existing forms of speculation. Clean Energy/Climate is another example of this, although it has torched many careers along the way and has the black swan risk of people quickly not caring based on politics.

Today the most visceral example is within TechBio where the Computational Drug Discovery platforms like Recursion continue to attempt to fulfill their promises of the last decade and the Synthetic Biology companies like Ginkgo search aggressively for the right PMF, outlasting a sea of companies that flew too close to the sun in 2021 and have since shut down.

With both of these areas of TechBio, we expect the world will only need to see 1-2 proof points crossing the chasm of promise to reality before they re-rate a collection of companies and venture investors aggressively pour money into these platforms in private markets at the growth stages (an area of the market which is near non-existent today).

The existentialism of narrative strategy

Over the past decade we have spilled a lot of ink at Compound trying to understand how narratives proliferate through technologies, clusters of talent, customers, and capital. While a decade ago it felt like a nice to have, looking across these phases, the core reality for founders is that narrative timing has become a first-order strategic decision that demands the same rigor as product, GTM, or research.

The compression of these cycles from 48 months to 12-36 months means founders have less room for error and must be more deliberate about when they emerge and how they position themselves relative to the ambient noise. Whether you’re defining a category in obscurity, carving out micro-narratives in the rising wave, fighting through peak fervor with relentless execution, or rebuilding credibility from the ashes, success increasingly depends on matching your narrative strategy to the specific physics of your moment in the cycle.

The companies that are best positioned often understand this synthesis and resource accordingly; treating narrative building as inseparable from company building rather than something that happens after product-market fit. In markets where competitors emerge quickly with scale, the ability to own mindshare through sophisticated narrative positioning has moved from incremental to existential.

Recent Comments