Now more than ever applied research1frontier tech? deep tech science? tech? companies must approach technology with a strategy and market positioning in order to survive the gauntlet of research, science, and engineering in order to bridge the R&D gap to commercialization and fundraising. In many companies, these strategies feel emergent, but at Compound we tend to believe they optimally should be thought of as intentional choices.

While we preach that companies must be relatively precise on the first 40 months of their milestones, how they align and execute on R&D/science alongside those milestones (and over the following 3-6 years) can have many gradients.

We believe there are two distinct and almost binary framings of R&D paths for companies, each with very meaningful implications on team building, fundraising, and overall company strategy. The best companies recognize this, but many die somewhere in the middle.

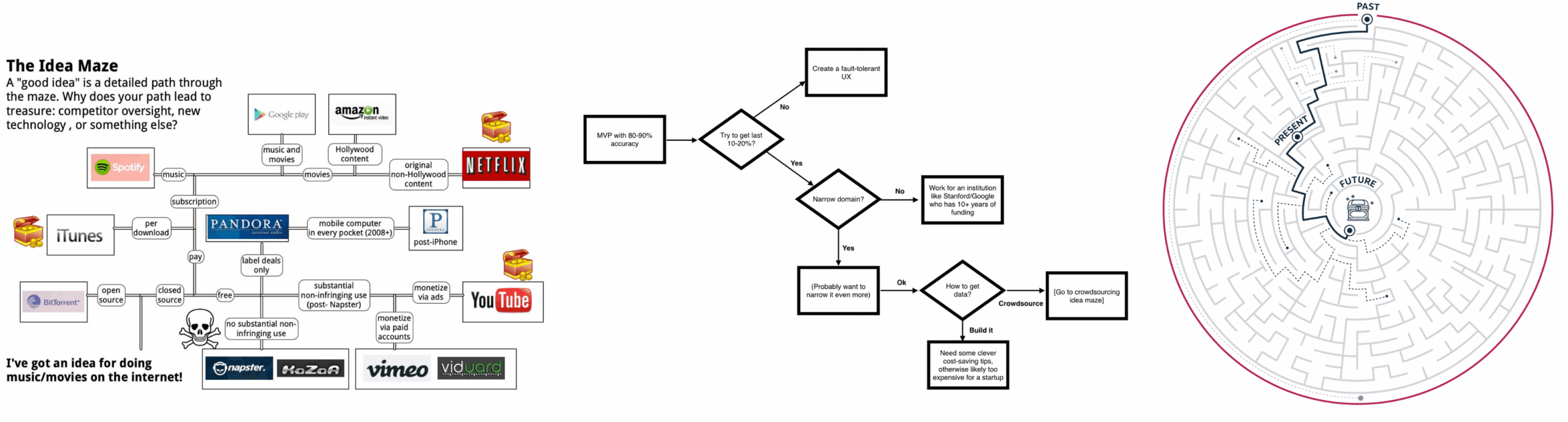

Sequencing & Perfect Idea Maze Navigation

Often the best applied research organizations are led by founders that have a high conviction vision of a certain future.

Some founders believe that in order to accomplish a multi-faceted goal (solve technical breakthrough, ship product around that breakthrough, scale commercialization of product) they must think carefully and understand how to knock out cascading technical and eventually commercial milestones in order to sequence to their future.

We can call this process Idea Maze Navigation which directly becomes trading optionality for compounding causality.

These companies are led by a person (or collectives of people) who have seemingly a supernatural grasp of the details of their company such as the pace at which research problems will be solved, the technical unlocks along the way, and much more,

This is incredibly difficult to do when as a company you are doing things that have literally never been done before.

These companies typically have a few things in common:

- High conviction on end market

- Low barriers to distribution if technology is built

- High degree of technical difficulty / non-consensus technical approach

In order to do this well these companies must:

- Have elite technical talent with a strong vision for commoditization curves in their given technology set – When doing things that have never been done before there is a high burden of proof that one can accomplish breakthroughs early on that allows the market to then extrapolate the ability to continue to have breakthroughs for many years.

- Build out leadership earlier to manage timelines – To the point above, good research talent does not necessarily equal on-time talent. When playing a multi-variable game across many years that you’ve explicitly laid out for the public (or privately) you need leader(s) to manage the core teams pushing across different vectors of R&D in an applied research org earlier on in the company lifecycle. These companies typically have narrow bands of error and thus having leadership that can “keep the train running on time” and recognize when timelines are slipping before it becomes existential is incredibly important.

- Be very good at forcing customer behavior change in their core market – Companies that are sequencing to precise futures often are doing so against a change in customer behavior. Technological breakthroughs might necessitate that incumbent buyers change their sales cycle time, their value leakage to startups, or their willingness to work with startups. This can mean being innovative on business models or on paths to commercialization as you ladder up with core customers through whatever variation of the LOI → production path your industry has.

- Have an elite ability to raise capital and control their technical narrative – Sequencing oriented companies must be exceptional at translating technical progress into legible narratives for various stakeholders. This narrative discipline compounds into fundraising advantages as these companies are typically appreciated by a subset of investors used to long time horizons and open-minded views on disruption, but the proof points are often very fuzzy, until they are not. Time horizons for legible proof points extend longer than most startups can survive without capital. This means you have to continually reinforce and reorient your narrative, demonstrate why certain technical milestones mean genuine de-risking even when commercial traction lags, and maintain strong relationships with early customer references who can validate the vision before the product fully exists.

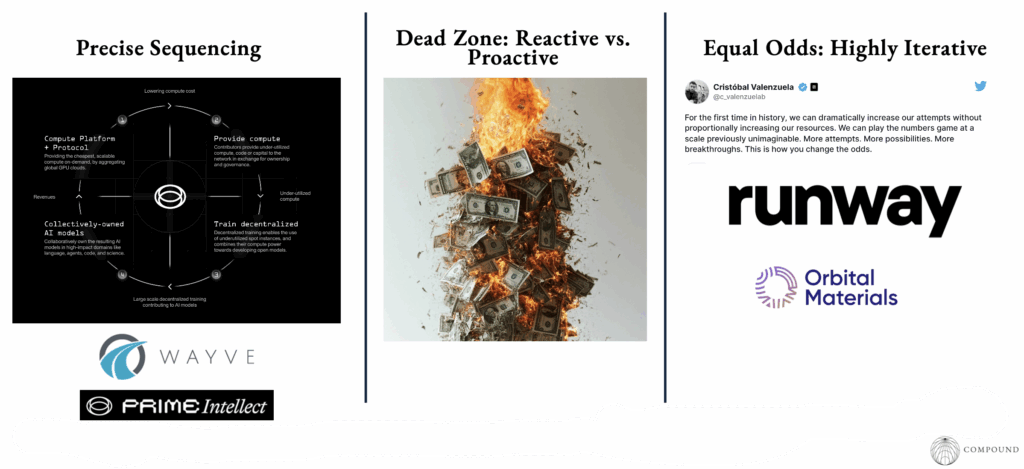

I have long loved these types of businesses and thus there are are countless examples in the Compound portfolio including companies like Wayve and Prime Intellect.2I’m not going to do the thing where I shill our entire portfolio so just use these as illustrative of others I’ve also written about Elon Musk’s Master Plans at length in my 2019 post, Narratives & Pseudosecrets, in which I quote him as saying “the main reason (I wrote the Master plan) was to explain how our actions fit into a larger picture, so that they would seem less random.”

In Pursuit of The Best Ideas: The Equal Odds Framework

There are other types of companies that sit at the opposite side of the “plan” spectrum which we can call Equal Odds Companies (a framing I’ve stolen from Cris at Runway).

The name references research on creative output showing that the probability of producing an influential work is roughly equal across all works produced. Quality emerges from quantity of attempts. Applied to company building, this suggests that in highly uncertain domains, producing more experimental iterations matters more than the precision of any single experiment. These companies know the future they are building towards but view high-degrees of projections as limiting factors or not dominant culturally.

Equal Odds companies typically have:

- High conviction on end goal (but uncertain customer sequencing) – Unlike a specific market or user per se, these companies often know what they are trying to do, but not necessarily who will use it or how it will resonate perfectly with a given customer.

- Ability to study and align with customers – Because of the lack of specificity above, these companies must sit closely culturally with their customers in order to ship the right features that accomplish the end goal and know how to drive fast adoption of new features/products in order to ship the maximum number of experiments (and get data from those experiments). These teams recognize technology is rarely a meritocracy in how it is adopted.3This customer intimacy must extend unusually deep into the organization. If you’re iterating rapidly based on customer signal, that signal can’t be filtered through sales or customer success layers. Research teams need unmediated access to how customers actually use the product.

- Organizational tolerance for productive chaos – These companies need systems that allow multiple parallel experiments without fragmenting the team. This often manifests in unusual org structures (novel roles, small autonomous groups, project-based teams that form and dissolve) rather than traditional R&D hierarchies. The cultural DNA has to support people working on things that might get killed in weeks.

- Maximal degree of product performance and thus difficulty. Simply, these teams must ship quickly and at high quality over and over again.

In order to do this well these companies must:

- Structure a research org as outcome/product oriented more than technical/publishing oriented for the duration of the company. This cascades into many of the other points but also has meaningful implications on hiring.

- Demonstrate accelerating commercial learning curves – Equal Odds companies must show consistent improvement in conversion metrics, retention, or revenue growth that proves rapid experimentation is working. The slope matters more than the absolute numbers early on. Investors and customers need evidence that customer proximity is translating into faster iteration cycles and better product decisions. Without this positive slope, Equal Odds companies look unfocused rather than experimental. The commercial traction becomes the proof that the organizational chaos is productive chaos.

- Acquire diverse types of talent. To the point above, when shipping a wide range of products that you are actively testing in close proximity to the end-industry or customer you’re serving, it typically means the DNA of the organization cannot be one of outsiders or “only tech”. We’ve seen this manifest with teams hiring more inter-disciplinary but less obvious hires as well as finding people who are less pedigreed on paper but show their work via portfolios, open source projects, or otherwise instead of via stops at elite institutions.

- Be elite at pressure testing ideas and iterating on them. There is a comfort with imperfection that comes with Equal Odds companies that often cannot be taught and must be a cultural base. With this imperfection comes a necessity to ship some novel and some “in distribution” ideas, and recognize when the novel should win out versus when the obvious product choices should win out. Founders of Equal Odds companies often straddle the line between deeply listening to the customer while also recognizing in paradigm shifts, the customer does not necessarily have the ability to imagine what they really want long-term.

Admittedly, early in my career these types of companies terrified me due to the unpredictability and often difficulty in understanding the time horizon in which the core insight will translate to strong PMF. Over time, one comes to realize that if the team is elite at the things mentioned above, and has incredible clarity of thinking and reasoning, the uncertainty is a feature.

Two examples in our portfolio include Runway who famously shipped 30 magic tools in 30 days (above) and Orbital Materials.4There are others…but still not going to shill the whole portfolio.

The In-Between Dead Zone

We tend to believe it is a death wish for founders to be caught in the middle of these paradigms. While it can feel most comfortable to “go slow to go fast” and bounce between these, there are structural decisions that must be made at the early and mid-stages of which type of company you are before you find PMF and “go all-in” proverbially. It is at this point this framework perhaps withers, but often this can be almost a decade into a company’s life.

The middle ground creates compounding organizational dysfunction. You end up mixing culture types across the org, hiring sequencing-oriented leaders who get frustrated by lack of clear milestones while bringing on iteration-focused ICs who feel constrained under attempts at long-term planning.

Your fundraising narrative becomes incoherent because investors can’t tell if you’re raising on a vision or on traction metrics.

Customers even can sense the uncertainty and delay commitments because they can’t tell if you’re building toward their specific needs or will chase something else at a moment’s notice. The confidence game that startups need to keep going falls apart.

The middle zone actively destroys the organizational trust and technical momentum that either approach requires to work.

What this framework actually means

I will once again say that choosing your path must come earlier in the lifecycle than many appreciate. Foundational decisions compound. Culture, early hires, investor base, customer relationships all encode assumptions about which game a company is playing.

To extend upon the points above, choosing a specific framework clarifies what kind of technical leadership you need. Sequencing companies benefit from people who have seen long-arc technology development before and can maintain conviction when proof points are sparse for extended periods. Equal Odds companies may want leaders comfortable with ambiguity, who can spin up and kill projects without mourning, and who judge research quality by product outcomes rather than technical elegance or pedigree. Of course, there are many other similar implications.

While this framework presents a duality, the macro environment of your category also matters.

As categories move quickly with higher rates of fundamental change, companies may be better suited to one mode versus the other. The most obvious example being for the past few years, almost all application-layer AI companies had to operate in some form of Equal Odds framework in order to be nimble alongside frontier model performance, expanding budgets, increased competition, and more.

Perhaps the most important point though is that the best founders understand their advantages and press on them.

Most founders building applied research companies don’t fail because they picked the wrong framework. They fail because they’re not honest about which one matches their actual operating mode, or they lack the conviction to commit fully to one approach. Startups with long paths of R&D are unforgiving of this kind of ambiguity and the market can feel it, waiting on any sense of incoherence to blow up the rocket ship on its way up.

Recent Comments