Pseudosecret – A non-obvious narrative about a next-order effect within your company, its path towards world domination, and the future you believe in.

In the very early-stages of a company, especially during a fundraise, narratives rule everything and pseudosecrets are the dominant way to build a narrative.

Counterintuitively, in some situations it can be a detriment to startups when you have an easy to understand or easy-to-form-an-opinion-on business when fundraising. The narrative creation mechanism can slide from the founders to a wider base of people, of which those people are often poorly informed or educated. If said narrative becomes widely adopted, it can make or break a fundraising process in the inefficient and often less-intellectual-than-we-think world of VC.

Early narratives create a spark that can quickly ignite a wildfire after a few pitch meetings and networking events during your fundraising process. There are countless examples of companies being deep in process with multiple funds, only for those funds to talk to each other, decide on a narrative, and all pass within hours or days of each other.

While wildfires are largely bad, this narrative can manifest itself both positively and negatively. Will the wildfire send your startup up in flames, or perhaps scorched earth the ground that your competitors are trying to build on?

For companies that are brand dependent (and thus decisions are more gut-driven or weak on immediate defensibility), often we can see a narrative spun around the founder.

VCs will say qualitative or high level things like “She is a killer” or “the product is magical.”

All of this helps people have a talking point that allows them to not have a particularly nuanced view but also say (in fewer words) “I get that this product has weak moats (or something intellectually flawed), but my job is to identify outliers, and in this case, the person is an outlier.”1These moats for brand/marketing driven investors seem to be real, but aren’t easily articulated. Multiple times I’ve asked elite consumer VCs to explain how they delineate a D2C company that will cap out at $10M in annual revenue vs. those that can scale to $100M+. I have yet to get a definitive answer.

In one of my least favorite cases of narrative transfer, people will take prior narratives for barely tangential companies and say things like “it’s like how Uber was for private cars at first but then moved to more affordable services!” This ignores the next-order effects that are often company dependent and is largely intellectually lazy, casting one outlier and domain transferring its path onto another.

Fast Narrative Shifts (On Demand Economy)

Source: Techcrunch

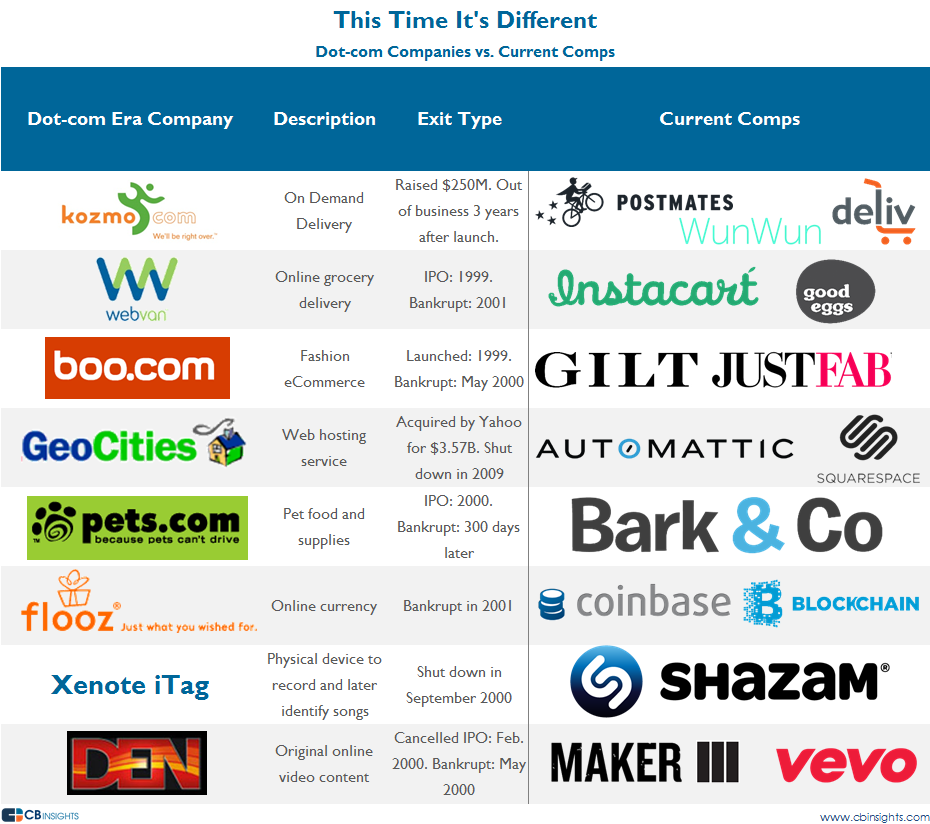

For companies that are in a given vertical, there can be specific narratives around paths to profitability that can kill companies. Around 2014, we saw a strong narrative spun around the on-demand economy surrounding growth, usage, shifting consumer demands, and ubiquity of new mobile-centric technologies like GPS that made it so that this time was different. By 2016, the narrative had quickly swung on the ODE startup ecosystem.

Most consumer spend categories now have a graveyard of ODE companies, with most notably those in the food delivery space continuing to battle out vs. incumbents (and those incumbents are struggling).

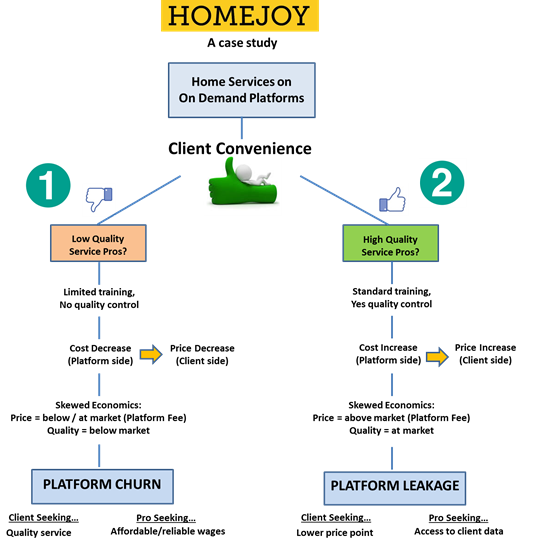

The narrative shift that we saw went from a story of growth and positive catalysts to one where tech broadly would debate unit economics, repeat usage, platform leakage, and would throw water on the ability to build a real business even when we reached those promised economies of scale.

Other Narrative Shift Examples

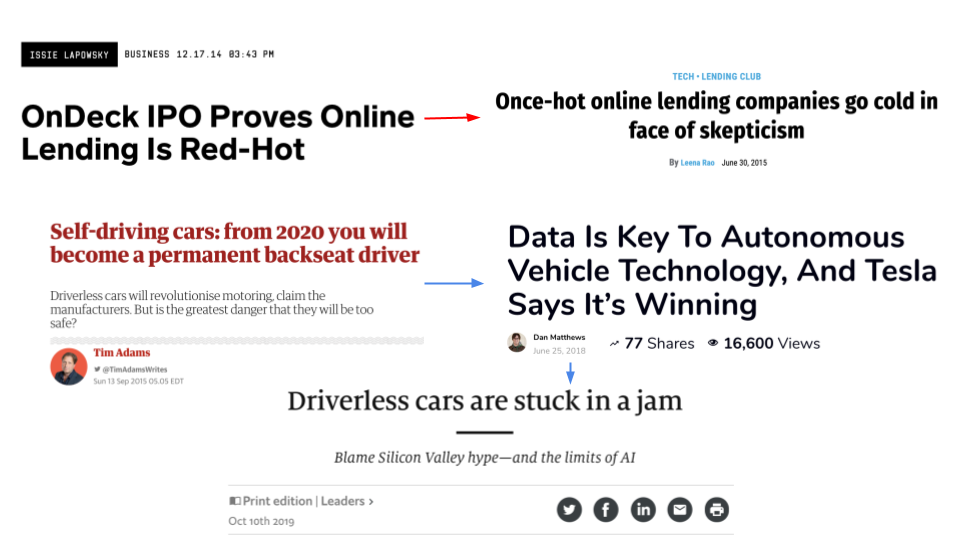

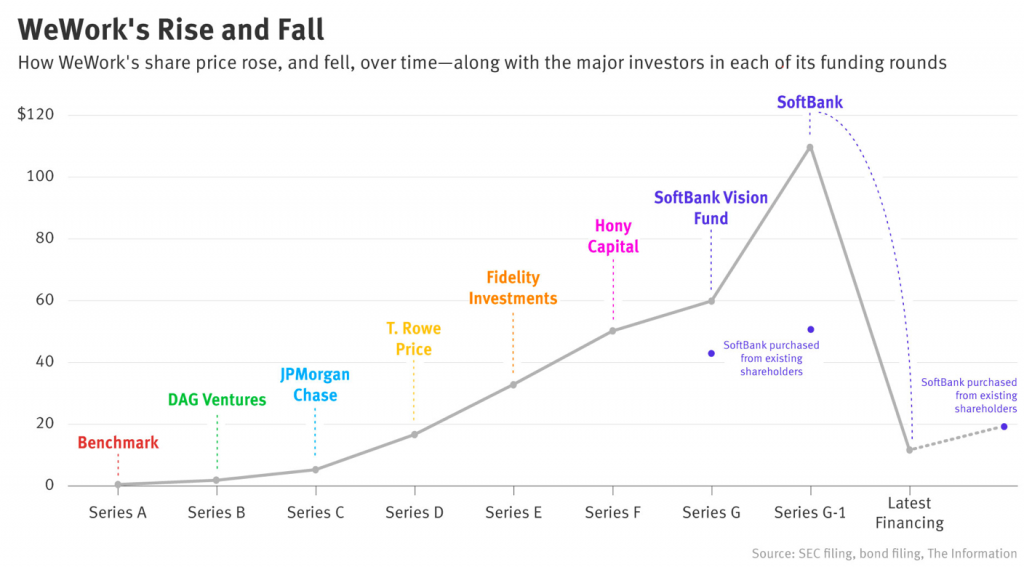

It is important to understand varying examples of how narratives can become truths. If we look into more recent history, we can study strong narrative shifts in areas ranging from Lending to Self-Driving Cars, and all the way to WeWork which saw a whiplash shift from the future of work to an overpriced, fraudulent, house of cards, in a matter of months.

We also see horizontal or industry-wide narratives spun that can be applied to specific company types and business models.

Deep learning-centric companies often push their narratives toward the importance of acquiring proprietary datasets, data network effects/data moats, and the flywheels that compound over time. This has recently been called into question by Martin Casado at A16Z, though is still a dominant narrative.

New healthcare clinic businesses have a strong narrative surrounding more efficient customer acquisition costs (CAC), an ability to monetize their patients/users in an outsized way due to brand or audience demographics, and cross-selling of other related products once they’ve built the trust due to their venture-subsidized and technology-centric above average Net Promoter Scores.

Networks for a long time have had a strong growth narrative that Chris Dixon calls “come for the tool, stay for the network.” This strategy builds on the idea of how to bootstrap a network by building a single utility and expanding the usage from single-player to multi-player in order to start the network effects flywheel.

We can continue to walk through examples across multiple companies, categories, and strategies, both positive and negative, however these are just a few that come to the top of my mind, and I’m sure you’ve heard various similar narratives repeated at events and on panels, podcasts, and in blog posts.

The important takeaway is that whether true or not, narratives will spread rapidly, and before you can shift your narrative, it will already have proliferated into a non-trivial percentage of the increasingly loud echo chamber of tech and sheepish venture capital ecosystem.

Dominating the Narrative WITH Pseudosecrets

Pseudosecret: A non-obvious narrative about a next-order effect within your company, its path towards world domination, and the future you believe in.

What I’ve found is that there are three ways in order to shatter or dominantly set narratives surrounding your company in the early stages.

The first, of course, comes from execution. Traction trumps all, however even moderate traction can quickly have cold water thrown on it by a strong or well-carried narrative (WeWork will do over $1.5B in revenue in 2019, doubling year-over-year).

The second way to capture a narrative is to build a company in a space that already has a strong narrative and thus is implicitly considered attractive to invest in and/or work at. As of this writing that may be areas such as no/low-code tools, collaboration software, machine learning infrastructure, wellness, and more. Yesterday that was the on-demand economy, D2C/DNVBs, and even AR/VR.

The third is to build a strong pseudosecret(s) and to incept your pseudosecret into people’s minds. A pseudosecret is a narrative about a next-order effect within your company its path towards world domination, and the future you believe in. It’s not the most obvious narrative, but is often the most important.

Pseudosecrets allow people to:

- Feel like they know a secret about your company (Even better if you can make an investor think they figured this out themselves vs. being told).

- Be able to combat doubters in a way that feels intellectually dominant and non-obvious.

- Paint a narrative that makes the upside future that you believe in feel closer to a reality/possibility.

Uber, Pseudosecrets, and a Ponzi scheme of ambition

So what’s an example of a pseudosecret?

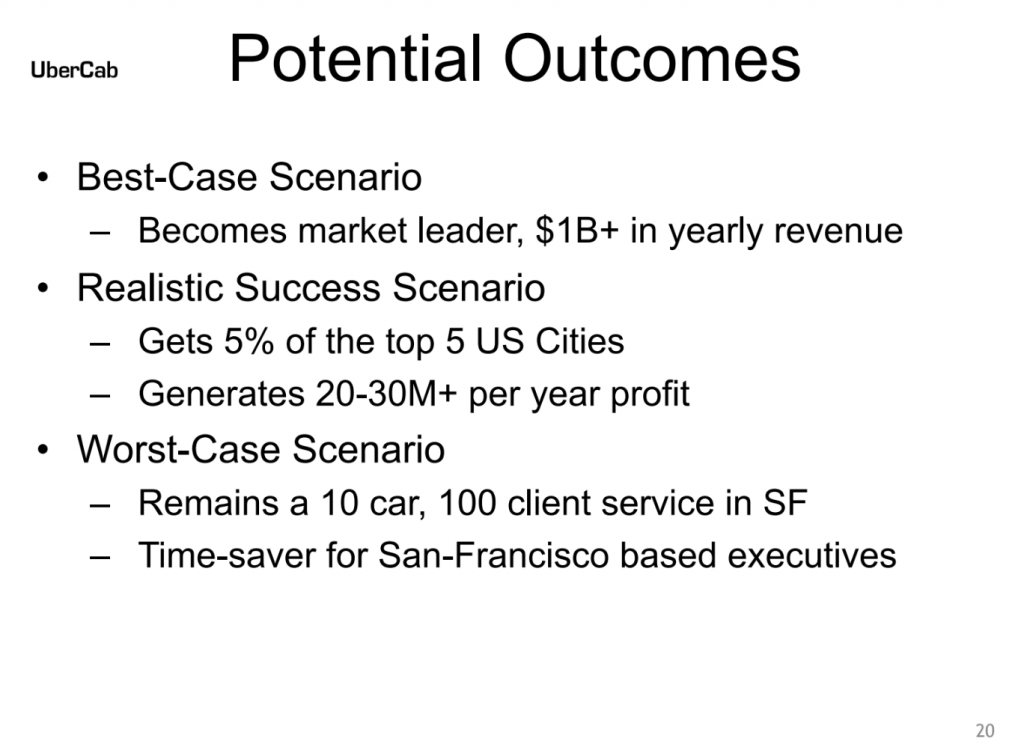

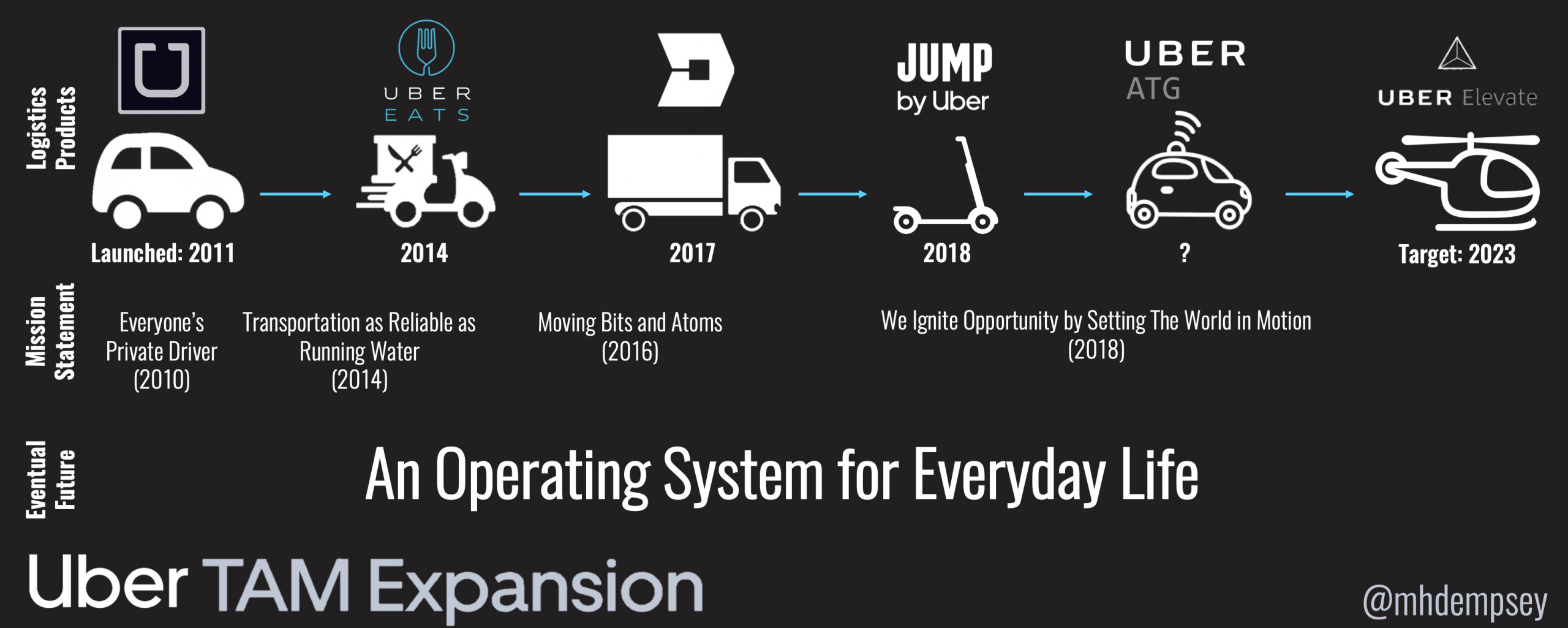

When Uber launched it was a mobile black car service. However the pseudosecret that got people increasingly excited was that by enabling easy ride-hailing via mobile, they were actually expanding the TAM of trips in a given city, an interesting insight that isn’t immediately clear when you think “black cars via mobile” or “everyone’s private driver”.

Once this pseudosecret became a clear narrative, Uber then shifted from a rideshare company to a routing and logistics company. During dinner conversation debates surrounding Uber’s valuation, people were bringing up the idea that a given Uber driver could have massive value if they also were moving other goods around a city, such as food.

The value of Uber Eats was born.

Over time we saw unit economics of Uber Eats come into question as other companies like Postmates and DoorDash also drew the ire of experienced tech people wondering how these companies were different than the 2000 comps, as well as how perhaps Uber Eats was even that unique or different from other food ordering platforms.

In the five years following Uber’s launch, the company continued to raise more capital as it promised investors grander visions both from a geographic expansion vector, as well as a vertical-centric vector. The company pitched visions of Uber self-driving cars (which Travis only thought of when he saw a Waymo vehicle. He later acquired Otto) and even Uber Air (air transportation) all while geographically expanding in an expensive, venture capital dependent manner, while battling against market share issues vs. competitors in multiple continents.

As Uber struggled with profitability, it became a strong narrative that if they could ever figure out autonomous vehicles (after its shiny Otto acquisition) they could change the economics of the food delivery business, and the booming freight business. In addition, the narrative surrounding whether or not all of these drivers were going to be continually classified as 1099 workers seemed to be increasingly existential to the business if regulation didn’t go their way. AVs would change the entire structure of their broader rideshare business from asset-light to asset-heavy, effectively eviscerating the heavily negative narratives. This was a pseudosecret that very few people wrote about or talked about years ago, but once it became a clear narrative, it has hung over the company as a party line since.

However as these various business lines faltered or faced delays, and as Uber continued to hemorrhage money, the company began to draw narratives of a Ponzi Scheme of Ambition. After a tumultuous few years, Uber barreled towards an IPO, and without profitability, needed a new pseudosecret that was grounded in reality and could stand the scrutiny of Wall St and other institutional investors.

“Some folks believe that the food category can be larger than the ride category … If that’s true … that would be an enormous win for us.”

Dara Khosrowshahi, CEO of Uber, Source

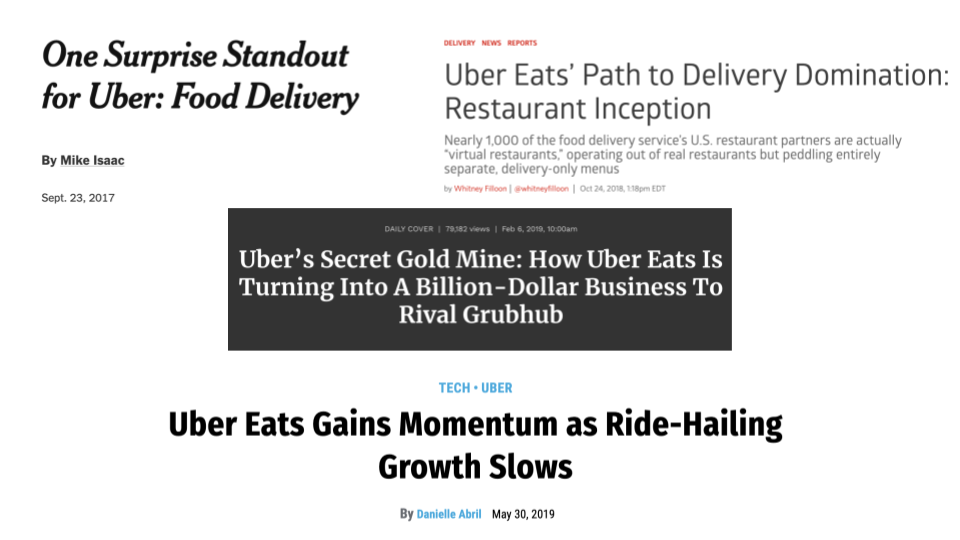

We quickly started to see a coordinated press push around how Uber Eats wasn’t just a logistics/ordering platform, but it also was a revolution in predictive dining in cities (and was growing incredibly fast). It could even become the most important part of Uber.

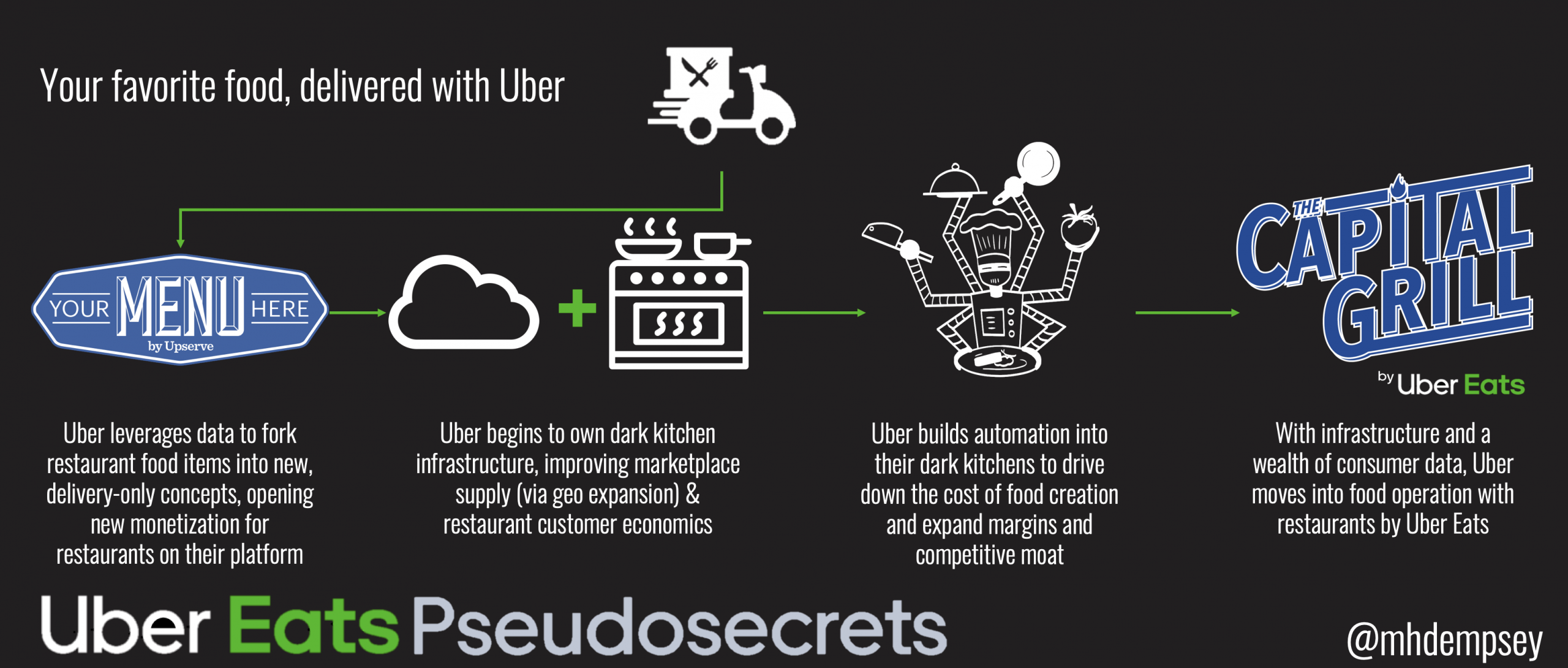

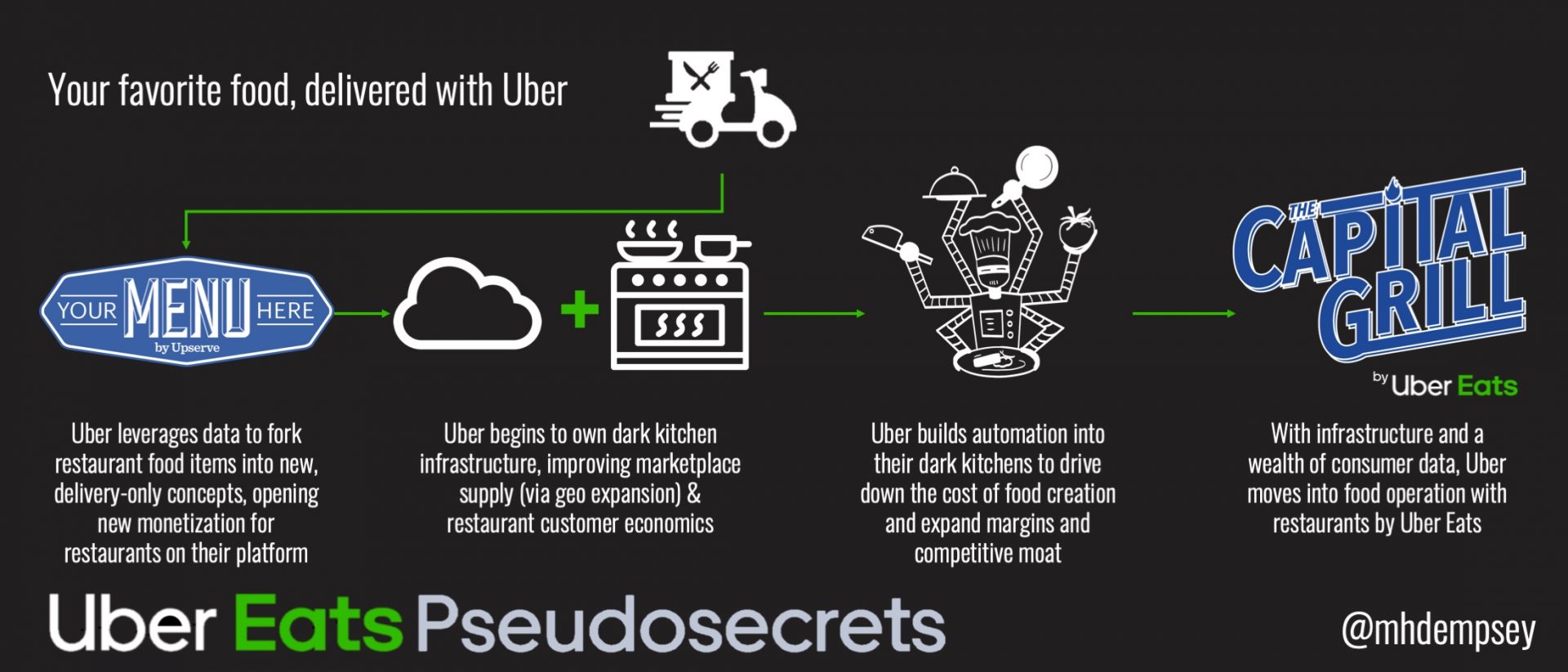

The obvious narratives were that food delivery was a macro trend, Uber Eats was growing incredibly fast, and could have potentially better unit economics than Uber. It was during this press push that Uber leaked their first pseudosecret surrounding Uber Eats. Uber Eats could tell restaurants what kind of restaurants they should be creating, based on their data. An incredibly interesting dataset that past companies like Seamless/GrubHub hadn’t meaningfully capitalized on in this space. It is my view that this narrative was created only to further kickstart a new pseudosecret plan of attack.

As of 2019 Uber Eats now has tremendous growth, the CEO saying that it could become bigger than the core driver of the business (that has hurt the stock post-IPO), and a really compelling narrative surrounding differentiation within Uber Eats because not only do they have a similar (and faster growing) dataset as incumbents like Seamless/Grubhub, but they also control the logistics layer too (which has pros and cons related to the workforce and economics that we won’t get into). The narrative even surrounding UBER was mentioning Uber Eats more and more.

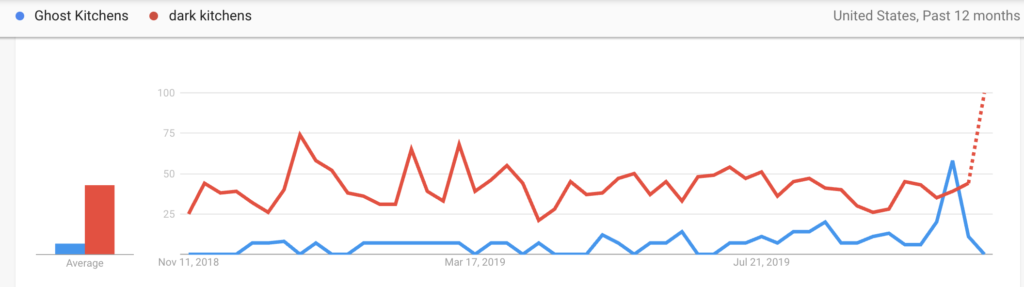

As we head towards 2020 we’re now starting to see increased chatter about a new pseudosecret surrounding dark kitchens/ghost kitchens and how as delivery proliferates throughout cities, the economic models of restaurants could shift. Uber is already shifting these models by telling restaurants to essentially fork their menus and spin up new brands within their same kitchens, so now we can make a case that Uber could also enable infrastructure surrounding dark kitchens, allowing brands that exist in certain neighborhoods or other geos to come into their infrastructure and serve their food with a lower opening cost (the Uber Eats moat grows) and better margins.

And a few years from now, the new pseudosecret is going to be about even more margin expansion, because you know those dark kitchens we were talking about? Turns out you can use automation to remove a large chunk of labor cost, and it’s more plausible than the past automation sell Uber made surrounding ATG.

So now it’s 2023 and over the life of its existence, Uber Eats (and its narrative) went from Your favorite food, delivered by Uber to Your favorite food menus from the restaurants near you, to Your favorite food, brought to you by dark kitchens and changed real estate economics, to Your favorite food, more profitable, enabled by Uber automation and eventually to…Your favorite food…owned by Uber: An Operating System for Everyday Life.

Pseudosecrets as a function of TAM Expansion

Pseudosecrets can be used for multiple forms of narrative building surrounding your company. The Uber example above specifically dives into pseudosecrets as a function of Total Addressable Market (TAM) expansion. These narratives paint a picture as to how a company can continually expand their TAM, and thus possible upside in enterprise value, by moving into new categories, use-cases, or lines of business.

TAM expansion pseudosecrets allow investors who deeply understand the value creation to underwrite their investments at a potentially higher exit value, and thus entry price, allowing them ability to win a deal (or a founder to minimize dilution).

They also can be helpful in times when companies are trying to continually raise capital while figuring out core mechanics of parts of their business (as we saw with Uber), as well as when they’ve capped out a given market value and look to continue to find growth and yield for new investors and/or the growth-hungry private markets.

Other Brief Case Studies on Pseudosecrets

Spotify and the verticalization of Audio

Another example that we can work through is the continued dominance of Spotify. Initially Spotify was riding the earliest waves of partnering with the pirate-devastated music industry in order to enable a new form of monetization of music. What the new all-you-can-listen business model did was shift music from an active to a much more passive listening experience. In a world of endless music, curation became increasingly important and Spotify knew how to algorithmically curate music to keep people listening (and thus dollars flowing via subscriptions) better than anyone2There is an argument to be made that Spotify may want people who actually don’t continually listen to music but do subscribe as they must pay out based on usage to artists. It’s a fair point, though not a behavior they’d prioritize over an active user base, especially not as they increasingly have near monopolistic pricing power.. It also further drove down the scarcity of music from a premium good to a bundled commodity.

As their global expansion continued and market share dominance grew, Spotify began to realize that this scaled data allowed them to in some ways commoditize music via the power of playlists. Today if you talk to anyone in the music industry, it is clear that playlist placement is a massive catalyst for many musician’s careers. But if Spotify can essentially pick and choose who within the long-tail rises largely at the expense of the fat head then they also can further verticalize and expand margins by owning a larger portion of the artists rights that they normally would have to pay out streaming costs to.

While this hasn’t been proven yet, it is clearly a dominant strategy in a playlist driven, commodity-centric music industry. There have been countless suspicions surrounding fake artists that could potentially be created by Spotify or similarly entities (a claim Spotify has denied).

Ultimately, if we are successful, we will begin competing more broadly for time against all forms of entertainment and informational services, and not just music streaming services.

Daniel Ek, Founder and CEO of Spotify,

Source: Spotify

As we look at the narrative arc of Spotify, we saw that they enabled music, then curated music, then commoditized music, then created music, and now owns the music industry. As Spotify looked up at the music industry and the growth of “hours listened” on a per user basis both on Spotify and off-platform, they saw that music was being complimented by other audio, largely podcasts. They swiftly made two acquisitions into the tooling and content spaces with Anchor and Gimlet. Spotify’s tentacles continue to push into the pseudosecret that they are now headed towards We Own Music to We Own Audio and eventually potentially to We Own Creative Content, via Spotify: Your Operating System for Entertainment (ok this one isn’t real but it’s a quiet question as to what media Spotify could further expand into). Based on Daniel Ek’s comments above, I suspect that if we weren’t in peak TV, we could have seen them push into film/tv on another timeline.

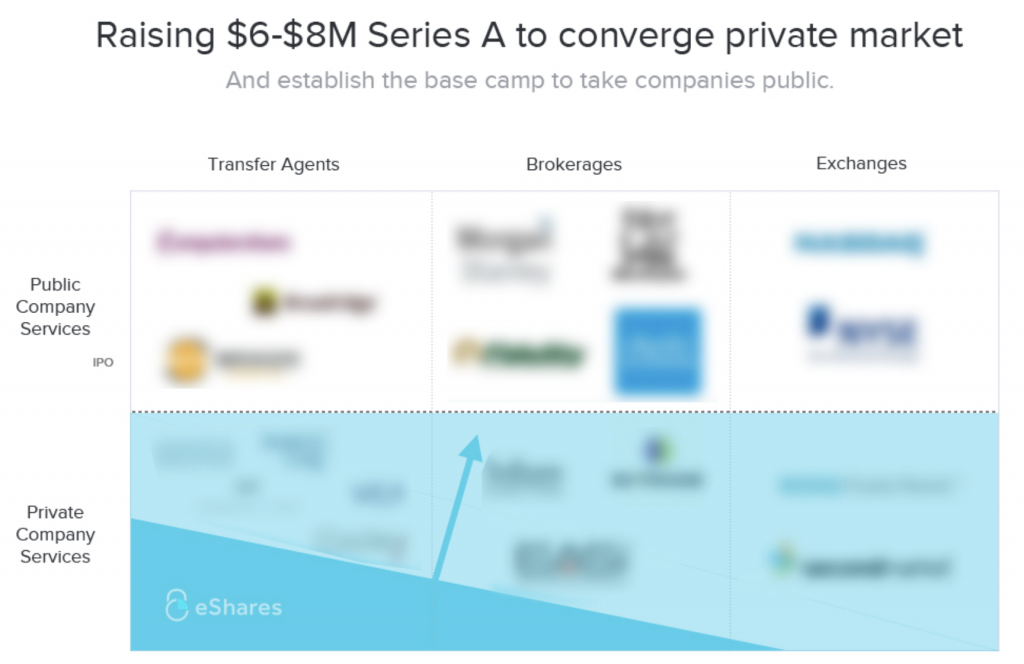

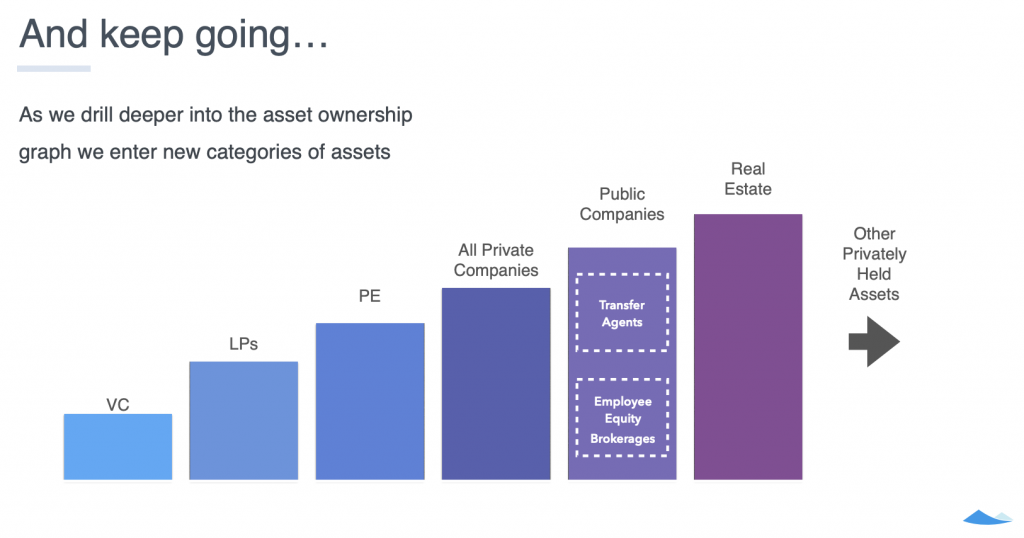

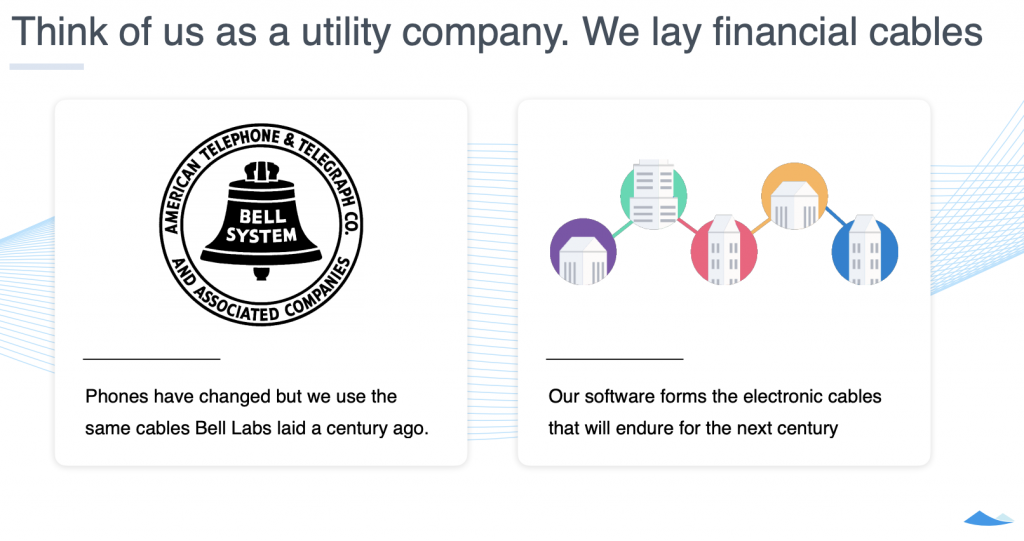

Carta & Changing Capital Markets

Another case study of pseudosecrets can be viewed within Carta. When Carta started (formerly eShares) they were a startup-centric product to manage the messiness of cap tables and startup financing/ownership documents. As their Series A deck states, they looked at the private markets and understood that there was a lot of value that could accrue if you could provide a singular service (cap table management) and layer other services on top of this ground truth data (like 409a valuations).

As both private market investors within venture capital as an asset class began to dramatically expand, Carta saw an opportunity to take this ground truth data and acquire customers from all sides of the transaction (startups, investors, lawyers). However, while this narrative felt obvious, many felt the product was potentially too narrow. Carta does something very interesting though, as they tipped their cap as early as their Series A deck with this slide:

From private markets up to taking companies public. We’ll come back to this.

What we then saw from 2015 to 2019 when Carta raised their Series B, C, and D round was a continued explosion of private market investors and capital, as well as a much deeper pool of liquidity within these markets.

Recently, Carta openly published their Series D deck which hints at the ability for their thesis of private market management becoming more productized across multiple asset classes. What they didn’t overtly say at the time is something often discussed in venture circles surrounding that Series A deck and startup liquidity.

As companies have opted to stay private for longer, a continual startup industry problem that hasn’t been properly solved has been productizing the secondary transactions and marketplaces for all of this private stock. It’s highly inefficient, can be legally costly, and the ground truth data is held in silos…unless you’ve spent the past 7 years gathering this data and building the pipes…like a utility company. And that is how Carta ended their Series D deck which they publicly announced in December 2018.

Carta raised a Series E in May of 2019 and along with the announcement came a retrospective on how Carta has walked through their vision of building their company over the years, and the pseudosecrets they turned into proven narratives along the way. In the post they break these down as going From Issuing Securities to Modernizing How Investors Manage Their Funds to Changing How Capital Markets Work.

Fortnite, Gaming TAM, and Social Networks

When Fortnite originally launched and took hold as a Battle Royale pivot from Save The World, we saw a lot of thinkpieces surrounding the explosion of the format as well as how Epic Games was going head to head with PUBG (among others). The narrative very much was centered on the rise of the Battle Royale format, the cultural moments surrounding dominant streamers like Ninja, and the continued monetization via free-to-play (and not pay-to-win) dynamics within the game.

Within tech and investor circles, people were underwriting Fortnite as a highly successful game with an increasingly popular format and monetization strategy, that was also bending the platform-centric dynamics that the gaming industry had been built on for decades prior. Fortnite had finally grown to be a game that was larger than the consoles themselves, Sony was forced to give in to cross-play, and mobile releases showed a scale of a game that we had never seen before.

What a small subset of smart people began to talk about was how these cultural moments and time spent in-game started to resemble not only gaming, but also social network behaviors. To underwrite Fortnite to the scale of the most successful game ever was a popular narrative, but to underwrite it to the scale, and possible enterprise value, of the next social network, media platform, and perhaps the first scaled metaverse (via an expanding Creative mode), was a different conversation entirely. The pseudosecret had begun to spread.

Fast forward to today and with the help of Matthew Ball’s post documenting Fortnite as a Metaverse, as well as many others, this now has become a mainstream narrative that underwrites a (small) portion of the $15B+ valuation that Epic Games is standing at today. Looking forward, I’m not sure what the core pseudosecrets are surrounding Fortnite, however we are increasingly hearing about the value of traditional media IP and gaming IP crossing over (a phenomenon we first saw at scale with Pokémon Go, and most recently have seen with League of Legends’ TV Show).

This new pseudosecret has fueled the narrative and countless tweets surrounding the TAM for gaming being larger than music and film combined, so it will be interesting to see where Fortnite and other key gaming properties go from here as they expand their ambitions perhaps from the digital world to the physical world.

Pseudosecrets as a function of SEQUENCING (AKA, THREADING THE NEEDLE)

When I meet a founder I always want to know what they think their business looks like in 1 year, 2 years, and 7-10 years from now. The middle isn’t immediately important, but the beginning helps me understand if I think they’ll be able to grow quickly and raise follow-on capital, and the later-stages help me understand what future they believe in. I then begin to understand how they think about sequencing (and thus, the middle) in order to achieve this ultimate future.

There are some companies that are entirely founded with this eventual future in mind and are embarking on the journey at a time that some may believe is too early or not realistic. These companies often are about attempting to pull a seemingly inevitable (in their mind) future closer in time by building core technology or infrastructure ahead of the market, or are built around reaching a future within certain capital constraints today.

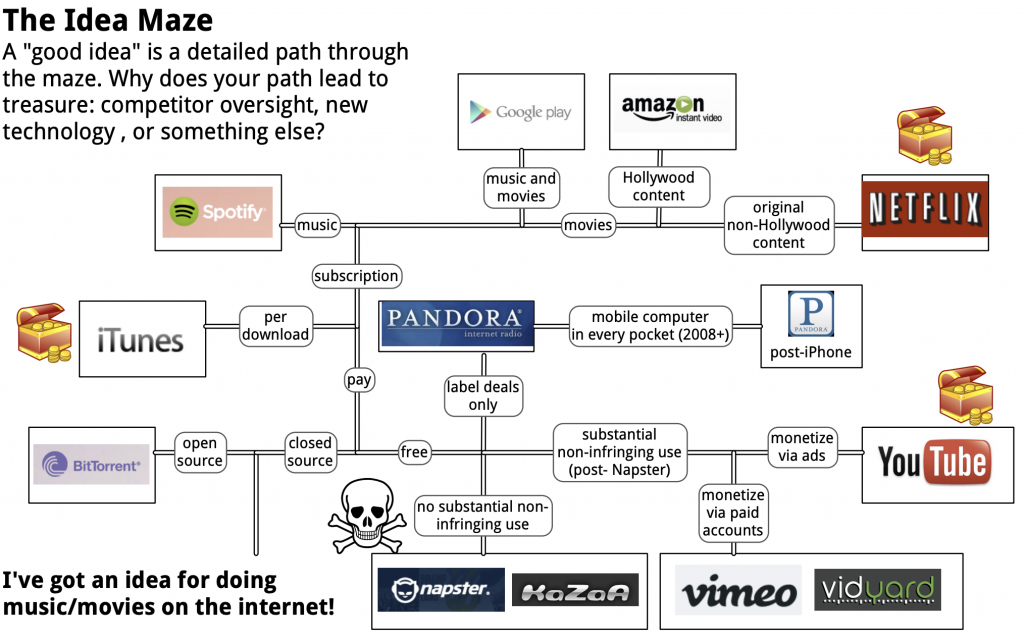

In order to do this, they must carefully sequence out how they are going to reach each enabling point in their business that unlocks the next step function of value creation, or merely allows them to continually survive and push forward. Balaji Srinivasan tangentially wrote about this awhile back and called it the “idea maze“.3Chris Dixon subsequently wrote about this concept again, citing Balaji, in 2013 He articulates the idea maze well in this paragraph specifically:

In other words: a good idea means a bird’s eye view of the idea maze, understanding all the permutations of the idea and the branching of the decision tree, gaming things out to the end of each scenario. Anyone can point out the entrance to the maze, but few can think through all the branches. If you can verbally and then graphically diagram a complex decision tree with many alternatives, explaining why your particular plan to navigate the maze is superior to the ten past companies that fell into pits and twenty current competitors lost in the maze, you’ll have gone a long way towards proving that you actually have a good idea that others did not and do not have. This is where the historical perspective and market research is key; a strong new plan for navigating the idea maze usually requires an obsession with the market, a unique insight from deep thought that others did not see, a hidden door.

Balaji Srinivasan: Market Research, Wiring, and Design

While the overarching concept of the idea maze gets at the crux of the idea of sequencing pseudosecrets, the core component surrounds the hard to see insight, which will allow any founder or investor a unique ability to envision the future they believe in coming to fruition.

Fortnite sits in an interesting place here as they stumbled upon Battle Royale, the subsequent usage, and have been putting out fires for the past year trying to keep it up. Whether or not they initially set out to build a metaverse or not, is debatable at best4I would argue they didn’t, which is why the case study is set above and not below., but one could argue that in order to build a metaverse in 2020, you would need a core application in order to drive usage and time spent in the world,5There’s an interesting case study when thinking about other metaverses to see how they’ve viewed this specific problem. Rec Room, I would argue, spent a lot of time curating the world with premium experiences, while continuing building games in hopes of finding their killer app. VRChat on the other hand built a vast and expansive world without many killer apps, that allowed it to become a place where internet culture was both birthed and scaled. I believe in the former strategy, especially if we think of the metaverse as truly living on a next compute platform (VR/AR), which has all sorts of issues surrounding on boarding users en masse to a new form factor and UI/UX. which would create demand for UGC outside of this singular world (the map), which would then enable a core economy to develop as account affinity increased (the skins), which eventually leads to a scaled economy and metaverse and/or new social network. This is where Tim Sweeney plans to take Fortnite, and Unreal broadly.

That said, there are better, more clearcut examples of how to utilize pseudosecrets for sequencing.

ELon MUSK’s SEQUENCING PSEUDOSECRETS (Tesla, SPACEX & sequencing for capital constraints)

However, the main reason (I wrote the Master plan) was to explain how our actions fit into a larger picture, so that they would seem less random. The point of all this was, and remains, accelerating the advent of sustainable energy, so that we can imagine far into the future and life is still good. That’s what “sustainable” means. It’s not some silly, hippy thing — it matters for everyone.

By definition, we must at some point achieve a sustainable energy economy or we will run out of fossil fuels to burn and civilization will collapse. Given that we must get off fossil fuels anyway and that virtually all scientists agree that dramatically increasing atmospheric and oceanic carbon levels is insane, the faster we achieve sustainability, the better.

Here is what we plan to do to make that day come sooner:

Elon Musk, Tesla Master Plan Part Deux

In 2006 Elon Musk wrote a post titled The Secret Tesla Motors Master Plan (just between you and me) where he set out to describe the next decade or so of Tesla’s plan toward a sustainable future. He very explicitly describes his future in the first paragraph stating:

“…the overarching purpose of Tesla Motors (and the reason I am funding the company) is to help expedite the move from a mine-and-burn hydrocarbon economy towards a solar electric economy, which I believe to be the primary, but not exclusive, sustainable solution.”

Ten years later, after proving the performance, and driving down the cost of electric vehicles, Musk wrote Master Plan, Part Deux, merging together SolarCity and Tesla6This was a highly controversial move that has resulted in multiple lawsuits and continues to come under scrutiny as Musk essentially self-dealing and saving a company he started, with his other company’s capital., and again, laying out the next wave of steps he needed to get to true sustainability and bring the future he believed in to fruition on a faster timeline.

Musk again ended this post with a clear, step by step plan:

“So, in short, Master Plan, Part Deux is:

Create stunning solar roofs with seamlessly integrated battery storage

Expand the electric vehicle product line to address all major segments

Develop a self-driving capability that is 10X safer than manual via massive fleet learning

Enable your car to make money for you when you aren’t using it“

At each of these decade long inflection points, Musk made a calculated bet to convert his pseudosecrets into clear narratives surrounding the company7 Whether it was for stockholders or capital issues is irrelevant to this post. The competitive moats of building a company like this8Moats are traditionally stronger in sequencing psuedosecrets vs. TAM expansion as you theoretically run into fewer issues of someone picking you off at the point of entry (a la Uber->UberEats you can get picked off by a Postmates vs. Tesla -> Electric Grid you usually are doing the first part in order to necessitate the possibility of executing the second. with the capital that Musk already had at his disposal, likely made him more willing to publicly expose his pseudosecrets.

Musk has similarly done this with his company SpaceX, and their eventual goal to colonize mars and make human life multiplanetary by driving down the cost of launch due to reusability, generating substantial cash flow via a telecom network9For a very in-depth read on how important StarLink is, read this piece by Casey Handmer (StarLink), enabling a privatized and economically viable space economy to emerge (due to continual launch and relay), creating core infrastructure for re-fueling on mars, and then allowing us to further explore and/or colonize planets.

Musk always frames these sequences as a way to bring these futures forward in economically viable ways. With Tesla he said: “The reason we had to start off with step 1 was that it was all I could afford to do with what I made from PayPal.” and more recently with SpaceX, while discussing BFR and becoming a multiplanetary species he said:

“the most important thing that I want to convey in this presentation is that I think we’ve figured out how to pay for it. This is very important. In last year’s presentation we were really searching for how to pay for this thing.”

Despite this, there are many other examples of companies utilizing pseudosecrets for sequencing planning, expansion, and long-term goal attainability. That said, they are harder to publicly examine as sequencing psuedosecrets often rely on heavier secrecy10I’m doing my best not to utilize any non-public intel that people wouldn’t be okay with me loosely writing about., are more often than not in areas without core infrastructure built out, and are predicated on an early view that is easy to revisionist history towards (because not every founder is going to write a blog post explaining what they are going to do over the next 2 decades).

Pseudosecrets NEED NARRATIVES, NArratives need execution

Narratives and pseudosecrets are a core component to the fuel of many of today’s most successful and important companies. When used properly, both can be some of your strongest and most potent ammunition for everything from hiring to business development to fundraising.

On the hiring front, a strong narrative can allow you to compete for top talent, increase the funnel of candidates, and build affinity towards the work employees are doing on a day-to-day basis, minimizing churn. Pseudosecrets will allow you to close competitive talent and show room for growth within your organization.

On the business development side, narratives and pseudosecrets will similarly enable your competition for customers, increase your top of funnel, and even perhaps minimize churn and give unfair advantages related to pricing power, contract length, and other monetization dynamics.

When fundraising, your narrative dictates what tier company you are viewed as by the market, while proliferation of your pseudosecrets can impact pricing and pace of process. As the number of startups raising capital each year continues to grow and rising fund sizes pushes investors towards larger desired outcomes, this ammunition will only help in standing out amongst a sea of competitors.

While narratives and pseudosecrets are incredibly powerful tools for use in the journey of building a company, what’s most important in consistent narrative building is ultimately execution. Execution at each core inflection point of a business enables continual narrative growth, and pseudosecret belief vs. erosion and doubt because in the end, narratives and pseudosecrets only accrue value to their relevant companies if they eventually become truths.

Thanks to KK, RWD, SD, and ZMH for thoughts while writing this.

Recent Comments